Pearl Harbor water poisoning: US military families say they continue to fall ill | Water

Beginning in December, US army Major Amanda Feindt and her family found themselves in and out of Tripler army medical center in Honolulu. First, her husband for debilitating ocular migraines, then her four-year-old daughter, who was vomiting with severe abdominal pain, then her one-year-old for chemical burns, and later herself when she started experiencing crippling back pain that prevented her from being able to walk, among other troubling symptoms.

The Feindts were only four of thousands who reportedly sickened after 19,000 gallons of jet fuel from the US navy’s second world war-era underground fuel storage facility leaked into one of Oahu’s main drinking water aquifers. The contamination has led to a major water crisis in the Pacific, affecting more than 93,0000 people.

Many affected military families and civilians at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam say they are continuing to fall ill and that the navy has not provided accurate information on the possible toxins in their tap water and their bodies.

This has led to calls for a rapid emptying of the tanks to prevent further disaster.

Feindt says her case is emblematic of the difficulties families face. Back in November, Feindt, alongside many others, were told by the navy that nothing was wrong with their water, despite an advisory from the Hawaii department of health’s (DOH) saying not to use the water to drink, bathe, wash dishes or brush teeth.

Not wanting to question her employer, her family continued to use the water for over a week, until the navy formally announced it was suspending the use of the fuel tank facility. Test results from the DOH subsequently showed the drinking water had petroleum levels 350 times higher than what the department considers safe.

Still, the navy declined to share results of testing done at her home and daughter’s school, and told her, she said, that she had to file a Freedom of Information Act request to receive them. (She is yet to receive those results. The navy could not comment on this issue, a spokesperson told the Guardian.)

In December, the military moved Feindt’s family, and other military families, to hotels in the area, where they stayed for months. In March, after flushing efforts to clear the water lines, and sampling 15% of the homes for residual contamination, the military and the Hawaii health department said it was safe to go home.

Returning residents have taken to Facebook to report seeing oil sheens on the water, alongside several reports of health problems such as skin rashes and chemical burns (particularly with children), neurological problems, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue and headaches, among other problems.

In early June, Feindt, who paid over a thousand dollars for her family’s toxicology screens with Great Plains Laboratory in Kansas, received hers, and posted some of the results for her two children in the support group. They showed a level of gasoline additives, flame retardant chemicals and petroleum. Several others received similar results. They have caused alarm.

The Guardian asked an independent toxicologist, Jenifer Heath, to interpret them, but Heath said it was impossible for her to do so without other information, such as the individuals’ medical histories.

Physical symptoms

The hydrocarbons in jet fuel have been linked to liver and stomach cancers, reproductive problems, nervous system and endocrine dysfunction, and neurological problems, said Chelsey Simoni, an epidemiological toxicologist from the HunterSeven Foundation, a non-profit group of medical professionals and military veterans, in a May letter to Armed Forces Housing Advocates.

Lawyers representing families who have filed lawsuits against the navy claim the Tripler medical center has only been treating symptoms, and not running in-depth toxicology screenings or considering the possibility of long-term issues.

Navy officials have said there is no evidence to suggest residents’ long-term medical symptoms are related to the water distribution system, and that nobody had been hospitalized due to petroleum toxicity. “I would not conjecture that families are making up their complaints,” Capt Michael McGinnis, surgeon for the US Pacific Fleet and senior medical officer, told Hawaii News Now. “Certainly stress can manifest in physical symptoms. That’s something to consider.”

A navy spokesperson, Lydia Robertson, told the Guardian that “we too are concerned about long-term health effects.” As a result it had set up an incident registry, and Hawaii’s military medical facilities were “well aware of our contaminated water event and are prepared to evaluate any associated medical concerns”. Robertson also said that, per the Hawaii health department, testing for petroleum hydrocarbons is “limited and not readily available”.

Most recently, the navy told Hawai’i News Now, there were no medical encounters in the last month related to the water crisis. (Some residents disputed this on social media, and say the navy helpline is ineffective.) The navy is also undertaking a water testing program of 15% of homes a month.

Leaks

The Red Hill underground fuel storage facility began construction just east of Pearl Harbor at the beginning of the second world war, not long before the Japanese attacked in 1941. US military presence on the islands is contentious among many Native Hawaiians, and has been since 1893, when the military aided in the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy.

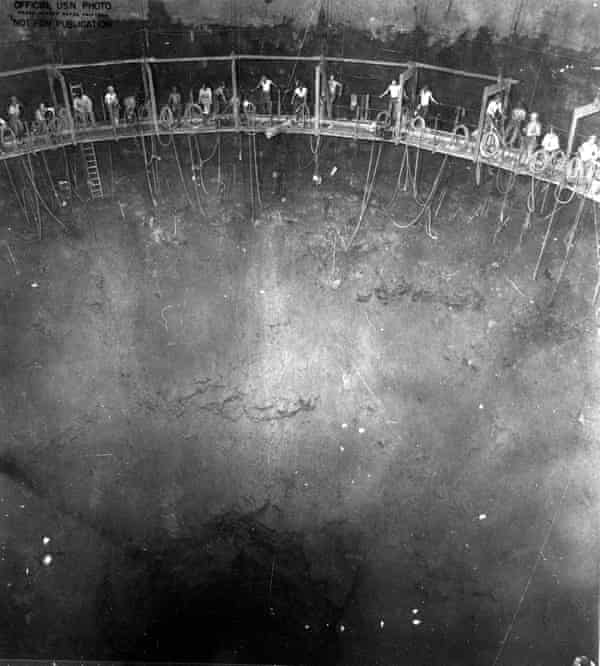

The facility contains 20 250ft-tall tanks, with the capacity to store 250m gallons of fuel, all 100ft above the city’s main aquifer.

The 2021 leak was not the first. A report prepared for the navy several decades ago quoted a former employee as saying 1.3m gallons leaked during the war. And in January 2014, the navy reported to the Hawaii health department that there had been a 27,000-gallon leak, which contaminated the area groundwater and brought attention to the facility and its threat to Oahu’s water sources.

Not long after, the military officials agreed with federal and state agencies to upgrade the corroded systems.

According to the EPA, infrastructure improvements began the day of their agreement. Even so, there was a series of smaller leaks – one of which was not reported by the navy for months to avoid bad optics.

A whistleblower also informed the local health department that navy officials withheld information about the extent of corrosion at the facility and provided false testimony about its structural issues.

These problems – coupled with a heavily redacted third-party assessment that says extensive repairs are needed due to heavy corrosion, cracking and fire risks – have many calling for the tanks to be defueled as quickly as possible.

“We’re one earthquake away from a complete lifetime, life-long, catastrophe,” said Wayne Tanaka, director of the Sierra Club of Hawai’i, which has been suing the navy since 2017.

It is not clear how long it will take to defuel the tanks. In a 2019 analysis, the navy claimed it could safely defuel tanks within 36 hours. But a new estimate, released as the navy admitted that extensive human errors and systemic failures led to the leaks, puts completion at the end of 2024.

Water protectors

Throughout the crisis, Feindt, who has served in the army for 16 years, has been one of the few active military members who have been outspoken on social media and the news. She says she has suffered retaliation from her superiors and other military personnel. (The army declined to comment on these allegations.)

She has found support from victims of the water contamination discovered in the 1980s at Marine Camp Lajeune in North Carolina, but most significantly from Native Hawaiian activists.

In December, the Oahu Water Protectors, a coalition of organizers and community members fighting for clean water, held a protest where hundreds showed up at the capitol, chanting “Ola i ka wai” (water is life) and demanding the shutdown of Red Hill.

The group has since been canvassing neighborhoods with brochures to raise awareness, waged social media campaigns, and is part of the Shut Down Red Hill Mutual Aid Collective. This primarily Hawaiian-led organization has provided military and civilian families with supplies and bottled water, and organized community meet-ups for families to talk about their struggles.

On 14 June, another group of community activists, the Wai Ola Alliance, filed a lawsuit seeking to have the court declare that the navy violated the Clean Water Act, with a $60,000-a-day fine for violations that have occurred since April 2017.

One of the leaders of the alliance is Mary Maxine Kahaulelio, who was one of several activists arrested in 1977 for trying to stop the US army bombing the Hawaiian island of Kaho’olawe. Such efforts eventually succeeded and the land was returned to the state in 1994. It is now a cultural reserve.

In recent testimony about another military training center, she brought up the significance of Pearl Harbor.

“Pearl Harbor used to be the greatest fishpond that Hawai’i had ever known. Pearl Harbor fed the ali’i’ [royalty], fed the commoners and it’s all gone, because the military owns all our land. But you don’t own me.”

She ended with an appeal to the military: “We love you, but aloha, go home. Go home.”